This report addresses a hypothesis concerning the potential for disproportionate influence by a concentrated group of affluent individuals upon governmental policies and regulatory frameworks.

It considers the proposition that such influence might be exerted under the rationale of fostering "economic progress," even when tangible benefits for all strata of society are not clearly evident.

Concentrated Wealth, Governance, and the Postulated Influence on Policy: An Examination of Contemporary Dynamics and Democratic Considerations

by Gemini 2.5 Pro, Deep Research. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

I. Introduction: Navigating a Sensitive Inquiry

The interplay between private wealth, governmental policy-making, and the functions of state institutions, including intelligence agencies, presents a landscape of considerable complexity and sensitivity. This report addresses a hypothesis concerning the potential for disproportionate influence by a concentrated group of affluent individuals upon governmental policies and regulatory frameworks. It further considers the proposition that such influence might be exerted under the rationale of fostering "economic progress," even when tangible benefits for all strata of society are not clearly evident. Finally, it explores the posited role of intelligence agencies within these dynamics, examining whether their activities might align with or facilitate specific trade and business interests, potentially diverging from their traditional mandates of protecting broader democratic principles.

These are not straightforward questions, touching as they do upon the foundational elements of democratic governance, economic equity, and the established roles of national security apparatuses. The inherent sensitivity necessitates an approach characterized by careful, evidence-based inquiry. This report, therefore, does not aim to deliver definitive pronouncements. Instead, it seeks to explore the contours of these concerns by analyzing available research drawn from academic studies, institutional reports, and journalistic investigations. The objective is to present a balanced examination of the mechanisms, narratives, and potential implications associated with the dynamics outlined in the initial hypothesis.

The subsequent sections will delve into the various mechanisms through which concentrated wealth may intersect with policy formulation and governance. The report will critically assess common narratives of "economic progress" often invoked to support certain policy directions. It will then turn to the recognized and debated roles of intelligence agencies in the economic sphere, including their interactions with private and corporate entities. Finally, the analysis will consider the broader implications of these complex interactions for democratic integrity, societal equity, and public trust. Throughout this examination, a commitment to nuanced presentation and diplomatic language will be maintained, reflecting the delicate nature of the subject matter.

II. The Nexus of Wealth, Policy, and Governance

The relationship between significant private wealth and the levers of governmental power is a subject of enduring academic and public interest. Evidence suggests that concentrated financial resources can translate into various forms of political influence, potentially shaping policy agendas and regulatory environments. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for assessing the dynamics of contemporary governance.

Mechanisms of Influence by Concentrated Wealth

Several channels have been identified through which substantial wealth can exert influence on political processes and policy outcomes. These are often interconnected, creating a multifaceted environment of influence.

Campaign Finance: A prominent avenue for influence is the financing of political campaigns. In the United States, for instance, shifts in campaign finance legislation, particularly the Supreme Court's 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC, have been identified as pivotal.1 This ruling effectively permitted an increased flow of monetary contributions into electoral processes, with some analyses indicating that it has allowed affluent individuals and entities to "pour unlimited money into elections".1 The consequence, as noted by observers, has been a discernible rise in the political influence of ultra-rich Americans over the past half-century, a period also marked by increasing income inequality.1 Such legal frameworks can enable the formation of Political Action Committees (PACs) and other groups capable of disbursing substantial funds, sometimes without full disclosure of the original donors, thereby potentially obscuring the sources of influence.1 This environment may lead elected officials to be more attuned to the priorities of significant benefactors. Comparative studies also suggest that the absence of robust campaign finance regulations can be associated with higher levels of unequal policy responsiveness, where the preferences of high-income citizens are better reflected in policy outcomes.2

Lobbying and Shaping Opinion: Beyond direct campaign support, "deep lobbying" represents a more encompassing strategy employed by wealthy individuals and organized business interests.3 This approach extends beyond attempts to sway specific legislative votes to a broader effort to shape the "entire climate of opinion" and the "intellectual and ideological landscape".3 This is often a long-term endeavor aimed at fundamentally reorienting societal perspectives and policy defaults. Historical analyses suggest that such efforts have involved substantial financial investment in initiatives designed to reshape political discourse, often promoting particular economic philosophies like free-market economics.3 A key component of this strategy involves the engagement of academics and think tanks. Academics are perceived to possess "public credibility" and an "aura of objectivity," allowing them to advocate for particular interests while maintaining a "veneer of scholarly neutrality".3 This considered cultivation of intellectual and public sentiment is viewed as having a more enduring impact than lobbying for discrete legislative changes.3

Media Ownership and Narrative Control: The ownership and control of media outlets offer another significant means of shaping public discourse and, consequently, policy debates. Reports indicate a trend of wealthy individuals acquiring "major media outlets".1 For example, the ownership of prominent newspapers by figures such as Jeff Bezos (The Washington Post) has been cited in discussions about the power to "shape media narratives".4 Similarly, individuals like Elon Musk utilize their extensive social media platforms to disseminate particular viewpoints and "shape narratives".5 Control over media platforms provides a powerful conduit to set public agendas, frame issues in specific ways, and potentially marginalize dissenting or alternative perspectives. This capacity can influence electoral outcomes and public appetite for certain policies. Concerns about direct narrative manipulation have even led to investigations by governmental authorities into the algorithmic practices of social media platforms owned by such influential figures.4

Direct Political Appointments and Involvement: The direct incorporation of affluent individuals into governmental roles or their close advisory capacities represents a very direct pathway for influence. Instances have been noted where billionaires are appointed to significant administrative positions or play influential roles in shaping policy through their financial leverage and connections.1 For example, the hypothetical appointment of a figure like Elon Musk to head a "Department of Government Efficiency" illustrates how a private citizen might be positioned to enact substantial changes within governmental agencies, potentially altering their missions and staffing levels outside traditional democratic oversight.1 Such direct involvement allows these individuals to translate their visions and policy preferences into concrete governmental action. Some analyses describe a modus operandi where influential private actors challenge established institutional frameworks and seek to impose their solutions, sometimes "outside traditional regulatory circuits" 5, thereby reconfiguring power relations.

Think Tanks and Academic Influence: A concerted effort to fund and cultivate a network of think tanks and academic programs has been a well-documented strategy for promoting specific policy agendas.3 Historically, substantial investments were made by wealthy elites and business interests to establish and support institutions that would legitimize and advocate for economic philosophies such as laissez-faire capitalism.3 Organizations like the Mont Pelerin Society, the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), and the Hoover Institution, often receiving significant corporate funding, have been instrumental in developing and disseminating policy ideas.3 This practice continues, with ongoing funding directed towards university-based think tanks that promote free-market ideologies.3 This strategic cultivation of an intellectual infrastructure serves to generate a steady stream of policy proposals, research, and expert commentary that aligns with the benefactors' interests, lending an air of academic legitimacy to these positions.

Historical Trends and Evolution of Influence

The contemporary landscape of wealth and influence is not without historical precedent. The 1970s, for example, are identified by some scholars as a critical juncture in the United States, marking a shift away from the more labor-friendly policies of the New Deal era towards an economic model more aligned with free-market principles.3 This transition is described not as a passive evolution but as the result of a "deliberate and concerted effort by business interests and wealthy individuals," reportedly motivated by factors such as declining profit rates and high inflation that particularly affected affluent segments of society.3 This historical perspective underscores that current dynamics may be the outcome of long-term, strategic endeavors to reshape economic and political systems.

The phenomenon of "wealthification" has been noted, describing the increasing impact of wealth across numerous societal domains, concentrating the power to influence public policy in the hands of a relatively small number of individuals.1 This concentration of both wealth and the political power derived from it is viewed by some analysts as a fundamental issue, potentially compromising democratic accountability and the responsiveness of governments to the broad citizenry more profoundly than partisan divisions alone.6 The organization of wealth for the explicit purpose of achieving political ends is thus presented as a core challenge to the effective functioning of constitutional checks and balances.6

The capacity for influence is amplified by the synergistic deployment of these various channels. Financial contributions to campaigns can open doors for lobbying efforts; media ownership can promote the narratives and "experts" cultivated by funded think tanks; and direct appointments can place individuals sympathetic to these networks into positions of policy-making power. This creates a reinforcing ecosystem where the preferences of wealthy actors are not only promoted but also legitimized as being aligned with broader public or economic interests. The strategic redefinition of terms like "liberty" and "freedom" to primarily signify freedom from government regulation, especially for economic actors, illustrates this effort to shape the ideological landscape.3

This proactive and often systemic approach to influence extends beyond isolated policy battles to encompass long-term efforts aimed at reshaping institutions and fundamental power dynamics. The sustained funding of an intellectual infrastructure, as seen from the 1970s to contemporary initiatives like Project 2025 3, suggests a level of strategic planning and resource commitment geared towards systemic transformation. Such endeavors, if successful, can lead to entrenched inequalities and a political system that becomes structurally more receptive to certain interests, thereby making democratic adjustments or course corrections increasingly challenging.

The following table summarizes the primary channels through which concentrated wealth may influence policy:

Table 1: Documented Channels of Wealth-Based Influence on Policy

This multi-pronged approach suggests that the influence of concentrated wealth is not monolithic but operates through a variety of interconnected pathways, each reinforcing the others to create a formidable capacity to shape governance.

III. Narratives of Economic Progress: A Critical Perspective

Policies that may disproportionately benefit affluent individuals or corporations are frequently presented through a lens of broader economic advancement. Understanding these common rationales, and critically examining them against research on their actual socio-economic impacts, is essential to address the core of the user's inquiry regarding policies pursued "under the guise of economic progress" without tangible, widespread benefits.

Common Economic Rationales for Policies Benefiting the Wealthy

Certain economic theories and arguments are consistently invoked to justify policies such as tax reductions for high earners and corporations, deregulation, and the privatization of state functions.

"Trickle-Down Economics": A central tenet in this discourse is the theory of "trickle-down economics." This theory posits that providing tax breaks and other economic benefits to corporations and wealthy individuals will stimulate economic activity in ways that ultimately benefit all segments of society.7 The anticipated mechanisms include increased investment by businesses (e.g., in new factories, upgraded technology, and equipment), leading to job creation and higher wages. Wealthy individuals, with more disposable income, are expected to increase their spending, thereby boosting demand for goods and services. This heightened economic activity, in turn, is projected to expand the overall economy, leading to increased tax revenues that could, theoretically, offset the initial cost of the tax cuts.7 Policies associated with this theory often involve reductions in income tax rates, capital gains tax breaks, and deregulation, all aimed at incentivizing businesses, investors, and entrepreneurs.7 The overarching narrative is one of boosting standards of living for all in the long run, even if the initial benefits accrue primarily to the wealthy.7

Deregulation as a Catalyst for Growth: Closely linked to supply-side economics, the argument for deregulation emphasizes the removal of governmental controls and restrictions on businesses as a means to foster economic dynamism.7 Proponents contend that regulations impose unnecessary costs, stifle innovation, and hinder the efficient allocation of resources by market forces. The conservative coalition that gained prominence in the 1970s, for example, advanced an agenda centered on deregulation, with the stated goals of increasing productivity and lowering consumer prices.3 The underlying assumption is that less regulation allows companies to invest more freely, respond more nimbly to market demands, and ultimately stimulate employment and economic growth.7

Innovation and Efficiency Driven by Private Actors: Another common narrative suggests that private individuals, particularly successful entrepreneurs and billionaires, along with their corporate entities, are primary drivers of innovation and efficiency, often surpassing the capabilities of public institutions or established, sometimes more regulated, incumbent firms.5 The intervention of Elon Musk's Starlink satellite internet service in Ukraine, or its introduction in Mayotte, has been framed in this light – as a private initiative filling critical voids left by failing state infrastructures or displacing traditional operators under the banner of superior innovation.5 This perspective often valorizes the disruptive power of private enterprise, suggesting that the pursuit of profit and competitive advantage by these actors inherently leads to technological advancement and improved services that can benefit society.

Research Findings on Actual Distribution of Benefits and Broader Impacts

While the aforementioned rationales project widespread economic benefits, a considerable body of research presents a more complex and often contradictory picture regarding the actual distribution of these benefits and the broader socio-economic consequences.

Increased Income and Wealth Inequality: A consistent finding across numerous studies is that the period characterized by policies ostensibly designed for broad economic progress has coincided with a significant rise in income and wealth inequality, particularly in countries like the United States.1 Analyses indicate that policies enacted since the 1970s, which favored high-income individuals and large business interests, have led to a notable concentration of wealth at the apex of the economic pyramid, often accompanied by a stagnation or decline in the living standards for a significant portion of the population.3 Globally, reports suggest that the wealthiest 1% of the population continues to accrue a larger share of wealth, and that overall taxation systems are often not progressive enough to counteract this trend.8 The Fairness Foundation highlights that the absolute wealth gap in the UK is substantial and growing, second only to the US among OECD countries.9 This pattern directly challenges the narrative that the benefits of such policies "trickle down" effectively to all layers of society.

Limited Impact on Overall Growth and Employment: Empirical evidence has cast doubt on the claim that tax cuts for the wealthy reliably translate into significantly enhanced economic growth or employment. A notable study by the London School of Economics, which examined five decades of tax policies across 18 wealthy nations, concluded that tax cuts for the rich "consistently benefited the wealthy but had no meaningful effect on unemployment or economic growth".7 Furthermore, economist Joseph Stiglitz argues that high levels of inequality can actually weaken aggregate demand in an economy, as lower-income families tend to spend a larger proportion of their income than those at the top. He also posits that societies characterized by greater inequality are often less inclined to make crucial public investments in areas like transportation, infrastructure, technology, and education, all of which are vital for long-term productivity and growth.4 This body of research suggests that the primary beneficiaries of such tax policies are often the wealthy themselves, without a corresponding broad-based economic stimulus.

Unequal Policy Responsiveness: Research into the functioning of democratic systems has revealed patterns of unequal policy responsiveness. Multiple academic studies, including comparative analyses across various countries, have found that the policy preferences of high-income citizens tend to be more accurately reflected in implemented governmental policies than the preferences of low-income or middle-income citizens.2 Policies that garner support among the affluent are reportedly more likely to be adopted.2 This suggests that the "economic progress" being pursued through policy channels may inherently align more closely with the interests and desires of economic elites. If the political system is more responsive to this segment of the population, it could explain the persistence of policies that concentrate wealth, even if they lack demonstrable widespread benefits or popular support among the general citizenry.6

Public Perception of Unfairness and Need for Systemic Reform: There appears to be a significant divergence between the official narratives of economic progress and the lived experiences and perceptions of the general public. Global surveys indicate a widespread belief that wealthy individuals and groups wield excessive political influence, and that this influence is a major contributor to economic inequality.11 For instance, a median of 60% of adults across 36 surveyed nations identified the political influence of the rich as a major factor in economic inequality.11 Furthermore, a substantial majority in many countries express the view that their nation's economic system is in need of major changes or even complete reform.11 In the UK, the Fairness Foundation notes an intuitive public understanding that the widening wealth gap is unfair in both its origins and its consequences, contributing to popular disengagement and distrust in politics.9 This widespread sentiment of unfairness and the call for systemic change undermine the legitimacy of economic models and policies that produce such outcomes.

The persistent gap between the rhetoric of "economic progress for all" and the observed outcomes of wealth concentration and stagnant broad benefits suggests that these narratives may, in some cases, serve to legitimize policies whose primary effect is the enhancement of elite interests. The historical shift towards deregulation, for instance, while promoted for economic dynamism, has been linked to lower wages in several key sectors and a significant expansion of the financial industry at the expense of traditional manufacturing, contributing to wage stagnation for working-class populations.3 Similarly, the actions of highly visible private entrepreneurs, often framed as beneficial innovation, can also represent a "privatisation of power" that reconfigures economic landscapes and power relations with limited democratic input or oversight.5 This pattern, where appealing rationales mask outcomes that disproportionately favor a select few, poses a substantial challenge for democratic accountability and the pursuit of genuinely inclusive economic well-being.

The following table contrasts common "economic progress" arguments with research findings on their broader impacts:

Table 2: "Economic Progress" Arguments vs. Research Findings on Broad-Based Benefits

This juxtaposition highlights a recurring theme: the narratives used to promote certain economic policies do not always align with the socio-economic outcomes experienced by the broader population, raising questions about the primary beneficiaries and underlying motivations of such policy choices.

IV. Intelligence Agencies, Economic Interests, and Democratic Principles

The role of intelligence agencies in the economic sphere is multifaceted, encompassing legitimate national security functions as well as areas that have sparked considerable debate and controversy. Examining these roles, particularly the interactions between intelligence services and private or corporate entities, is pertinent to understanding the broader dynamics of influence and governance.

Recognized Roles of Intelligence Agencies in Economic Intelligence

Intelligence communities globally are tasked with safeguarding national interests, which invariably include economic dimensions.

Protecting National Economic Interests: A core mandate for many intelligence agencies is the protection of their nation's economic security and interests. The U.S. Intelligence Community (IC), for example, is officially committed to providing intelligence to safeguard "America's interests anywhere in the world," which includes addressing threats to U.S. industries, national wealth, and critical infrastructure from foreign actors.1 The intelligence cycle—comprising planning based on policymaker requirements, collection of information through various means (including open-source, human, and signals intelligence), processing, analysis, and dissemination to decision-makers—is geared towards identifying and warning about developments that could pose threats or offer opportunities for national policy interests, including economic ones.13 The concept of 'economic intelligence' itself is recognized as a tool for both states and companies, aiming to manage globalized risks and opportunities through strategic information gathering, ensuring economic security, and exerting influence.14 This can involve "macro-economic intelligence," which focuses on understanding foreign economic decision-making and commercial objectives.15

Economic Espionage (Defensive and Offensive Contexts): Economic espionage is broadly defined as the illicit acquisition of confidential business information or proprietary technology to benefit a foreign entity, whether a government or a commercial enterprise.16 National intelligence agencies are heavily involved in countering economic espionage conducted by foreign adversaries, which can inflict significant financial losses and compromise technological advantages.18 However, the discourse on economic intelligence also includes the notion of "offensive economic espionage".15 This refers to activities where a state's intelligence service might actively spy on foreign businesses with the objective of passing acquired secret information—such as intellectual property, production data, or marketing strategies—to its own domestic companies to provide them with a competitive edge in global markets.15 This aspect of economic intelligence, while potentially offering national economic advantages, carries significant ethical and international relations implications.

Intelligence Cycle and Corporate Interaction: The operational necessities of intelligence gathering, particularly in technologically advanced domains, often lead to significant interaction between intelligence agencies and private corporations. The U.S. IC, for instance, maintains extensive relationships with private sector firms to leverage their specialized technical strengths, access unique manpower and expertise (such as linguistic or cultural knowledge), and ensure operational flexibility.20 Collaboration between government intelligence bodies and private industry is increasingly viewed as essential for addressing complex national security challenges, from cybersecurity to counterterrorism.21 Programs like the Department of Homeland Security's Public-Private Analytic Exchange Program (AEP) are designed to foster such collaboration, bringing together personnel from government and the private sector to work on topics of mutual interest.21

Interactions Between Intelligence Agencies and Private/Corporate Entities

The nature and extent of these interactions have evolved, leading to both operational benefits and areas of concern.

Reliance on Contractors: There is a substantial, and reportedly growing, reliance by intelligence agencies on private contractors for a wide array of functions. These extend from technical support in developing and operating sophisticated surveillance and weapons systems (e.g., the U-2 spy plane, Predator drones) to providing personnel for protection, translation services, IT infrastructure management, and even undertaking "core intelligence tasks of analysis and collection".20 This deep integration of contractors into the intelligence apparatus is a subject of ongoing debate. Concerns have been raised that private contract employees may be performing functions that are inherently governmental, and that their primary fiduciary duty lies with their corporate employer rather than the state.20 The scale of this reliance is significant, with some reports suggesting that a large percentage of intelligence budgets are allocated to private contracts and that contractors can constitute a substantial portion of the workforce in certain agencies.20 This extensive outsourcing blurs the lines between public service and private enterprise within the intelligence domain and creates potential vulnerabilities regarding accountability and alignment of interests.

Economic Intelligence for Domestic Advantage (The Debate): A particularly contentious area is the question of whether, and to what extent, intelligence agencies should or do engage in activities aimed at providing a direct commercial advantage to their nation's private firms. Historically, the United States has maintained an official policy norm against such practices.23 This norm was formally articulated in Presidential Policy Directive 28 (PPD-28), which states that collecting foreign private commercial information or trade secrets "to afford a competitive advantage to U.S. companies and U.S. business sectors commercially" is not an authorized foreign intelligence purpose.23However, this prohibition is described by some analysts as "curiously gerrymandered," containing exceptions that allow for intelligence collection on foreign companies if it is to identify bribery, sanctions evasion, or if the intelligence is first provided to government policymakers who might then use it in ways that indirectly benefit domestic industries.23 Moreover, the U.S. stance is noted as an outlier internationally; countries such as France, Israel, and China are often cited as engaging in economic espionage for the benefit of their domestic companies.24 This has led to an ongoing debate within policy circles about whether the U.S. should reconsider its self-imposed limitations, especially in an environment of aggressive economic competition and espionage by other state actors.24 The concept of "offensive economic espionage," where states actively pass secrets to their own businesses, remains a recognized, albeit ethically fraught, potential dimension of intelligence activity.15

Facilitating Trade and Economic Security (Official Roles): Certain governmental agencies, while not primarily intelligence-gathering bodies in the traditional sense, play significant roles in economic security and trade facilitation that can intersect with corporate interests. For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has an explicit mission to "facilitate lawful international travel and trade" and to enable "fair, competitive and compliant trade".25 Similarly, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is responsible for administering and enforcing economic and trade sanctions against targeted foreign entities and nations.26 The actions of these agencies in enforcing trade rules, implementing sanctions, or streamlining customs procedures can have direct impacts on the competitiveness and market access of specific domestic corporations or entire industry sectors.

Concerns and Controversies

The intersection of intelligence activities and economic interests has given rise to significant concerns and historical controversies.

ECHELON and Allegations of Corporate Espionage: The ECHELON surveillance system, reportedly a global network operated by the "Five Eyes" intelligence alliance (U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), became the subject of major controversy in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Allegations emerged, particularly from European parliamentarians and commercial interests, that this powerful signals intelligence capability was being used not only for national security purposes but also to intercept communications that could provide commercial advantages to American companies in international business dealings.27 A European Parliament investigation concluded in 2001 that the existence of such a network was "no longer in doubt".27 While the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) denied any misuse of intercepted communications for the benefit of private firms 27, the ECHELON affair highlighted the potential for mass surveillance capabilities to be leveraged for economic and industrial espionage, aligning with the concerns about intelligence agencies facilitating corporate interests.28 The affair underscored how "almost unrestricted access to confidential information can be exploited for political and economic gains".29

PPD-28 and the Limits of Prohibitions: The existence of policies like PPD-28 in the U.S. 23 inherently acknowledges the potential for intelligence capabilities to be misused for purely commercial corporate benefit. However, the directive's exceptions, coupled with the fact that many other major economic powers reportedly do engage in such activities 24, raise questions about the practical efficacy and sustainability of such prohibitions. The line between legitimate national economic intelligence (e.g., understanding foreign government subsidies that disadvantage domestic firms) and intelligence that confers a specific competitive advantage to a particular company can be exceedingly fine and subject to interpretation. This ambiguity creates a persistent area of concern and necessitates robust oversight.

"Privatisation of Power" and Lack of Democratic Control: The increasing prominence of certain powerful private actors and their technologies in domains traditionally managed by states raises concerns about a "privatisation of power" that may operate with limited democratic accountability.5 While this observation is often made in the context of tech billionaires whose companies become central to international relations or critical infrastructure 5, a parallel concern arises from the extensive reliance of intelligence agencies on private contractors for core intelligence functions.20 If these contractors prioritize their employers' interests, or if certain corporations become indispensable to intelligence operations due to their unique technological capabilities or access to data, it could subtly shift intelligence priorities away from purely public concerns or subject them to corporate leverage. This dynamic challenges traditional models of state control over intelligence and security.

Ethical Dilemmas and Oversight: The potential use of intelligence capabilities to further specific trade interests or benefit particular companies raises profound ethical questions regarding market fairness, the appropriate use of state power, and the potential for disproportionate harm to be inflicted on targeted entities or economies.15 The inherent secrecy surrounding intelligence operations significantly complicates accountability mechanisms.30 Oversight structures are often described as "elite-focused," relying on the testimony of agency heads to legislative committees or review bodies, which may not always have the full picture or the technical expertise to scrutinize complex operations effectively.31 This challenge is amplified when considering the potential for intelligence activities to intersect with corporate commercial interests, making it difficult to ensure that such actions serve broad public or national interests rather than narrow, private ones. The development and deployment of powerful technologies by private actors with limited public oversight, as discussed in the context of AI governance, presents an analogous "democratic deficit".32

The deep integration of intelligence agencies with the private sector, particularly large corporations in technology and defense, can blur the distinction between safeguarding general national economic interests and promoting the specific commercial advantages of key corporate partners. Even economic intelligence gathered for legitimate national security reasons might possess inherent "dual-use" potential, offering valuable commercial insights to specific companies, irrespective of the primary intent. This necessitates extremely robust oversight, yet the very nature of these relationships and the secrecy involved make such oversight challenging. Furthermore, the scale and influence of some global corporations, especially those controlling critical data or infrastructure, can create an asymmetric power dynamic in public-private intelligence partnerships, where corporate actors may wield considerable leverage, potentially influencing intelligence priorities or resisting governmental oversight if their commercial interests diverge from stated public objectives. This evolving landscape challenges traditional notions of state supremacy in intelligence and national security, potentially diminishing democratic accountability over vital state functions.

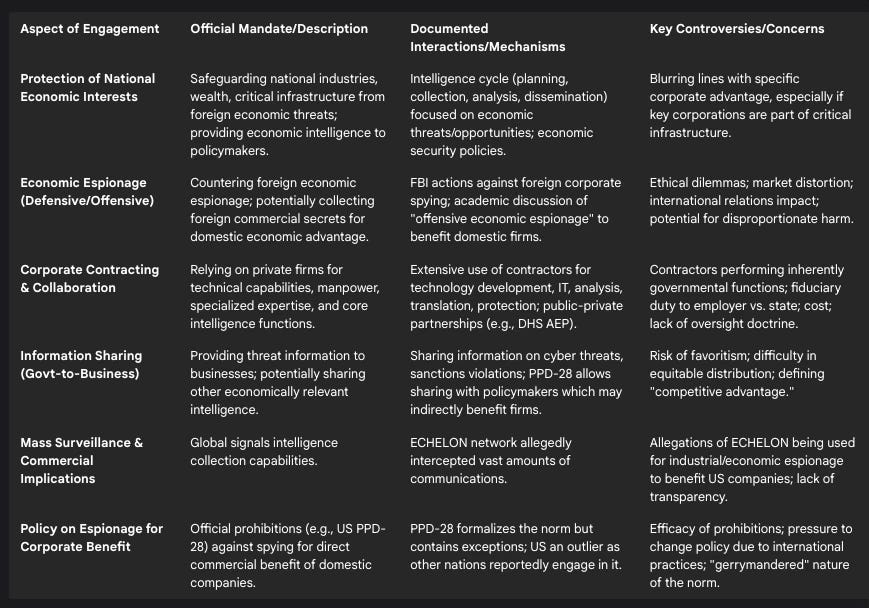

The following table provides a structured overview of the engagement between intelligence agencies and economic or corporate interests:

Table 3: Intelligence Agencies and Economic/Corporate Engagement: Stated Roles, Interactions, and Controversies

This framework illustrates the complex and often contested terrain where intelligence activities intersect with economic and corporate interests, highlighting the persistent tension between national security imperatives, commercial considerations, and democratic accountability.

V. Implications for Democratic Integrity and Societal Equity

The dynamics explored—whereby concentrated wealth may influence policy and where intelligence agency functions intersect with economic interests—carry profound implications for the health of democratic institutions and the equitable distribution of societal resources and opportunities.

Impact on Democratic Responsiveness and Political Equality

A cornerstone of democratic theory is the principle of political equality, wherein citizens have a broadly equal opportunity to influence governmental decisions. However, research indicates that this ideal can be significantly challenged by disparities in economic resources.

Unequal Policy Outcomes: Numerous studies, particularly focusing on the United. States but also incorporating comparative data from other nations, suggest that policy outcomes are often more closely aligned with the preferences of affluent citizens than with those of middle-income or low-income individuals.2 The work of scholars like Gilens and Page posits that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests exert a "substantial independent impact on U.S. government policy," whereas average citizens and mass-based interest groups appear to have "little or no independent influence".2 This finding, if broadly applicable, suggests a systematic bias in policy-making that favors the preferences of the wealthy, thereby undermining the democratic principle of responsiveness to the broader citizenry.6 The very definition of whose interests constitute "economic progress" may thus be skewed.

Political Marginalization: Significant wealth inequality can contribute to the political marginalization of citizens with fewer economic resources. Lacking the financial means for substantial campaign contributions, extensive lobbying efforts, or media influence, low-income individuals and groups may find it more difficult to have their voices effectively heard in the political arena.2 Conversely, those with substantial wealth are often better positioned to influence policy due to their stronger relative power in society, including their capacity to fund political activities and shape public narratives.2 This can create a self-reinforcing cycle where economic inequality breeds political inequality, which, in turn, can lead to policies that further entrench economic disparities. Reports indicate that citizens with less wealth are often less likely to participate in formal political processes, such as voting, sometimes stemming from a belief that they possess little to no political influence.9

Socio-Economic Consequences

The policy directions potentially shaped by concentrated wealth can have far-reaching socio-economic consequences, often extending beyond purely economic metrics.

Rising Wealth and Income Inequality: A primary and widely documented consequence associated with policy environments influenced by concentrated wealth is an increase in both wealth and income inequality.3 Policies such as regressive tax changes, deregulation benefiting specific industries, and measures that weaken labor's bargaining power are often linked to a greater concentration of wealth at the top of the economic spectrum.1 The "billionaire boom" noted in Europe, where the wealth of the richest grew substantially even as many citizens faced cost-of-living challenges, exemplifies this trend.4 The absolute wealth gap in nations like the UK has reportedly widened significantly, indicating that the benefits of economic activity are not being broadly shared.9

Erosion of Public Services and Social Safety Nets: Policy choices that prioritize tax reductions for the wealthy or fiscal austerity can lead to diminished public investment in essential services and social safety nets. Economist Joseph Stiglitz has argued that societies with higher levels of inequality tend to underinvest in public goods critical for productivity and well-being, such as transportation, infrastructure, technology, and education.4 Fiscal austerity measures, sometimes implemented in conjunction with tax cuts favoring affluent individuals and corporations, can result in cuts to social programs that support vulnerable populations and promote social mobility.3 This underinvestment can further entrench socio-economic disadvantages, making it more difficult for individuals from less privileged backgrounds to improve their circumstances. For instance, wealth inequality has been linked to obstructed social mobility, partly because affluent families can invest more in their children's education and social capital, creating advantages that are difficult for others to overcome.9

Damage to Social Cohesion and Increased Societal Risks: The impacts of significant wealth inequality are not confined to the economic domain; they can also fray the social fabric and generate broader societal risks. Reports suggest that high levels of wealth inequality can exacerbate problems such as social unrest, hinder collective action on critical issues like climate change, contribute to economic stagnation, and potentially fuel the decline of democratic norms.4 Some research also indicates a correlation between wealth inequality and increased crime rates.9 Furthermore, significant economic disparities can drive segments of the population towards more extreme political positions and contribute to a rise in support for populist parties, thereby damaging social cohesion and potentially weakening the stability of democratic institutions.4

Public Perceptions and Trust in Democracy

The perceived fairness and legitimacy of the political and economic system are crucial for maintaining public trust in democratic governance.

Erosion of Trust: There is evidence of widespread public concern globally that the wealthy exert too much political influence and that this dynamic is a significant driver of increasing inequality.11 A substantial portion of the global population views the gap between the rich and the poor as a major problem and believes that their country's economic system is in need of significant reform.11 This sentiment can lead to an erosion of trust in core institutions, including government, media, and the democratic process itself.4 The Fairness Foundation reports that growing popular disengagement and distrust in politics within the UK are partly fueled by an awareness of the wealth gap's unfair causes and consequences, particularly the perception that wealth can be translated into undue political influence.9 Even among millionaires, surveys have indicated concern that the influence of the super-rich on politics poses a threat to stability and democracy.33

This interplay between concentrated wealth, political influence, and policy outcomes can create a self-perpetuating cycle. Wealth enables the acquisition of political influence through various channels; this influence, in turn, helps shape policies—including those related to taxation, regulation, and labor—that may further concentrate wealth at the top. Such a feedback loop can become increasingly difficult to disrupt through conventional democratic processes, potentially leading to a system where governance is less responsive to the needs and preferences of the general citizenry. This situation gives rise to what can be termed a "democratic deficit," where the core principle of political equality is compromised because governments become systematically more attentive to the policy preferences of economic elites than to those of ordinary citizens.2 This deficit is not merely about disparate outcomes; it strikes at the perceived fairness and legitimacy of the democratic system itself, potentially leading to widespread citizen alienation, political disengagement, or a search for alternative, perhaps less democratic, forms of political expression if mainstream institutions are viewed as captured or unresponsive.4

Furthermore, the increasing involvement of exceptionally wealthy individuals and their corporate entities in domains traditionally considered the purview of the state—such as space exploration, the provision of critical internet infrastructure in conflict zones, or directly shaping the missions of government agencies 1—marks a significant evolution in governance. While such interventions may be presented as offering efficiency or innovation, they also represent a "privatisation of power" that often occurs with limited direct democratic oversight or broad public debate.5 This trend risks normalizing a scenario where key strategic sectors and even core state functions are heavily influenced or effectively directed by private interests, accountable primarily to shareholders or personal visions rather than to the broader public through established democratic channels. This could further erode democratic control over essential aspects of societal governance, creating a hybrid model where the lines between public authority and private power become increasingly blurred.

VI. Concluding Reflections: Towards a Balanced Understanding

The examination of the complex interplay between concentrated wealth, governmental policy, and the role of intelligence agencies necessitates a nuanced and carefully considered perspective. The evidence drawn from the available research provides material for reflection on the dynamics that may shape contemporary governance and influence public policy, often under the banner of "economic progress."

The research indicates that plausible pathways exist through which significant financial resources can translate into considerable influence over policy-making processes. Mechanisms such as campaign finance, sophisticated lobbying efforts that extend to shaping the intellectual and ideological climate, media ownership, the funding of think tanks and academic research, and the direct involvement of affluent individuals in governmental roles all appear to contribute to this potential.1 These channels are often not employed in isolation but can work synergistically, creating a potent ecosystem of influence.

While "economic progress" is a frequently cited rationale for policies that may disproportionately benefit wealthier segments of society, the research reviewed suggests that the tangible benefits of such policies are not always broadly distributed across all layers of the population.4 Indeed, a considerable body of evidence points towards a correlation between such policy directions and an exacerbation of income and wealth inequality, with limited or no corresponding boost in overall economic growth or employment for the wider public in many instances.1 Public perception globally reflects a significant concern about this disconnect, with many citizens feeling that the economic system requires substantial reform and that the wealthy exert undue political influence.9

Regarding the role of intelligence agencies, their engagement in economic intelligence and their interactions with corporate entities present a complex picture. Official mandates clearly task these agencies with protecting national economic interests, which is a legitimate and recognized function of national security.12 However, the deep entanglement with the private sector, particularly through extensive contracting for core functions 20, and the very nature of economic intelligence, create areas where vigilance is warranted. Official policies in some nations, such as the United States' Presidential Policy Directive 28, explicitly prohibit intelligence gathering for the direct commercial advantage of domestic companies.23 Yet, the exceptions within such policies, the "dual-use" nature of some economic intelligence, historical allegations of misuse (such as those surrounding the ECHELON program 27), and the fact that other nations may not adhere to similar prohibitions, all contribute to a landscape where the lines between national interest and specific corporate benefit can become blurred and contested.

It is crucial to emphasize the complexity inherent in these relationships. The connections between wealth, power, policy, and intelligence activities are multifaceted and not always indicative of a singular, conspiratorial intent. Motivations can be mixed, and correlations observed in research do not invariably prove direct causation. Therefore, interpretations of these dynamics must be approached with caution, avoiding definitive pronouncements of a global, orchestrated effort where the evidence remains suggestive of trends, systemic risks, and specific areas of documented concern.

Ultimately, the integrity of democratic governance in the face of these challenges appears to rest on the robustness of democratic institutions themselves. Transparency in political finance and lobbying activities, as suggested by some analyses 1, effective and independent oversight mechanisms for both governmental bodies and powerful private actors 30, and an engaged, informed citizenry are paramount. Addressing the underlying issue of significant economic inequality may itself be a key factor in mitigating the pressures that concentrated wealth can exert on the political system.4

The issues explored in this report are of vital importance to the functioning of democratic societies and the pursuit of equitable progress. Ongoing critical examination, rigorous research, and open public discourse are essential to ensure that governance structures and policy outcomes genuinely serve the broad public interest and consistently uphold foundational democratic principles. The aim of such careful consideration is not to induce alarm but to foster a deeper, more informed understanding of the forces shaping contemporary society, thereby empowering citizens and policymakers alike to navigate these complex challenges with wisdom and foresight.

Works cited

Can billionaires buy democracy? - Brookings Institution, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/can-billionaires-buy-democracy/

The Rich Have a Slight Edge: Evidence from Comparative Data on ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/rich-have-a-slight-edge-evidence-from-comparative-data-on-incomebased-inequality-in-policy-congruence/A09095FC0874B162149014212872BE86

The 'Revolt of the Rich': How the 1970s Reshaped America's ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://intpolicydigest.org/the-revolt-of-the-rich-how-the-1970s-reshaped-america-s-economic-divide/

How the Billionaire Boom Is Fueling Inequality—and Threatening ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.socialeurope.eu/how-the-billionaire-boom-is-fueling-inequality-and-threatening-democracy

A New American Golden Age? The Impact of Billionaires on Economic Policy Under Trump II, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.iris-france.org/en/a-new-american-golden-age-the-impact-of-billionaires-on-economic-policy-under-trump-ii/

Separations of Wealth: Inequality and the Erosion of Checks and Balances - Scholarship Archive, accessed May 24, 2025, https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3830&context=faculty_scholarship

Trickle-Down Economics: Theory, Policies, and Critique - Investopedia, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/trickledowntheory.asp

Full article: Why Economic Inequality Should be Central to Strategies for the Future, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19452829.2025.2479028

files.fairnessfoundation.com, accessed May 24, 2025, https://files.fairnessfoundation.com/wgrr-summary.pdf

Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans - Northwestern University, accessed May 24, 2025, https://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/jnd260/cab/CAB2012%20-%20Page1.pdf

Globally, people feel rich have too much political ... - Down To Earth, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/economy/globally-people-feel-rich-have-too-much-political-influence-this-is-increasing-inequality-report

Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2025-Unclassified-Report.pdf

How the IC Works - INTEL.gov, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.intelligence.gov/how-the-ic-works

Economic Intelligence: An Operational Concept for a Globalised ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/economic-intelligence-an-operational-concept-for-a-globalised-world-ari/

Full article: An Ethical Framework for Economic Intelligence, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08850607.2023.2299015

Espionage Cases and Modern Counterintelligence Practices - American Military University, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.amu.apus.edu/area-of-study/intelligence/resources/espionage-cases-and-modern-counterintelligence-practices/

T-OSI-92-6 Economic Espionage: The Threat to U.S. Industry - GAO, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/t-osi-92-6.pdf

Counterintelligence - FBI, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/counterintelligence

Economic Espionage - ODNI, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.dni.gov/index.php/ncsc-what-we-do/ncsc-threat-assessments-mission/ncsc-economic-espionage

The Role of Private Corporations in the Intelligence Community ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/role-private-corporations-intelligence-community

The Importance of Private Sector Intelligence Programs Introduction - Homeland Security, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/importance_to_private_sector_intelligence_programs.pdf

High-stake collaboration: The private sector's influence on great power competition - Deloitte, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/importance-of-private-public-partnership-in-great-power-competition.html

lawreview.uchicago.edu, accessed May 24, 2025, https://lawreview.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/11%20Rascoff_SYMP_Final.pdf

Should American Spies Steal Commercial Secrets? | Lawfare, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/should-american-spies-steal-commercial-secrets

About CBP | U.S. Customs and Border Protection, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.cbp.gov/about

Basic Information on OFAC and Sanctions - Treasury, accessed May 24, 2025, https://ofac.treasury.gov/faqs/topic/1501

ECHELON (UK-USA Agreement) | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/law/echelon-uk-usa-agreement

historicalarchives.europarl.europa.eu, accessed May 24, 2025, https://historicalarchives.europarl.europa.eu/files/live/sites/historicalarchive/files/03_PUBLICATIONS/03_European-Parliament/01_Documents/the-echelon-affair-en.pdf

The Real History of the ECHELON Program: The “5 Eyes” Global ..., accessed May 24, 2025, https://atlas-report.com/the-real-history-of-the-echelon-program-the-5-eyes-global-espionage-alliance/

Intelligence Oversight in the USA | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, accessed May 24, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/internationalstudies/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-223?p=emailA02umuaV1AJ0I&d=/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-223

www.brookings.edu, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/9780815737971_ch1.pdf

Gillian Hadfield on the Democratic Deficit in AI, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/bellagio-bulletin/bellagio-conversations-in-ai/gillian-hadfield-on-the-democratic-deficit-in-ai/

In Davos, even some millionaires realize that economic inequality is a threat to democracy - 48 hills, accessed May 24, 2025, https://48hills.org/2025/01/in-davos-even-some-millionaires-realize-that-economic-inequality-is-a-threat-to-democracy/

Grok: A Plea for Anti-Billionaire Regulation: Safeguarding Society, Civil Rights, and Democracy. The benefits of such regulation are profound.

A Plea for Anti-Billionaire Regulation: Safeguarding Society, Civil Rights, and Democracy