Despite the differences in context, certain underlying appeals and tactics employed by extremist movements demonstrate a degree of continuity. The scapegoating of minority groups...

Exploiting national anxieties, economic grievances, or feelings of cultural displacement. The use of propaganda and disinformation, tailored to the communication technologies of the era...

The Shadow of Pragmatism: Post-War Recruitment, Modern Extremism, and the Defense of Democracy

by Gemini Advanced, Deep Research with 2.5 Pro. Warning: LLMs may hallucinate!

Introduction

This report addresses the complex historical questions surrounding the post-World War II utilization of personnel with Nazi affiliations by the United States and its Allies, particularly concerning the motivations behind programs like Operation Paperclip and the establishment of the Gehlen Organization. It examines the claim that these actions constituted a form of "infiltration," analyzes the documented influence and ethical dimensions of integrating such individuals into Western structures, and evaluates the persistence of related ideologies or networks. Furthermore, it draws an analogy between this historical context and the rise of contemporary global far-right networks, exploring their ideologies, methods, and collaborations. Finally, synthesizing historical lessons and contemporary expert analysis, the report concludes with potential strategies for non-authoritarian societies to protect themselves against extremist threats. The analysis relies exclusively on publicly available sources and scholarly interpretations, aiming for an objective assessment grounded in historical evidence.

The report proceeds by first examining the geopolitical context of the immediate post-war era, focusing on the shift from defeating Nazism to confronting the Soviet Union, which fundamentally shaped Allied priorities. It then delves into the specifics of Operation Paperclip and the Gehlen Organization, detailing their objectives, execution, and the significant ethical compromises involved, including the deliberate obscuring of participants' pasts. Section two assesses the influence of key recruited individuals like Wernher von Braun and Reinhard Gehlen, evaluates the effectiveness and limitations of Allied denazification efforts in Germany, and critically examines the evidence regarding the persistence of Nazi-related networks or ideologies within Western institutions, directly addressing the "infiltration" narrative. Section three shifts focus to the contemporary landscape, analyzing the ideological foundations, mobilization tactics (both online and offline), and transnational collaborations of modern global far-right movements. Section four draws explicit comparisons and contrasts between the post-war integration of Nazi-affiliated personnel and today's far-right networks, highlighting both historical echoes and crucial divergences. The final section synthesizes lessons from historical responses to extremism and contemporary expert recommendations to outline strategies for strengthening democratic resilience against such threats.

Section 1: The Post-War Nexus: Cold War Imperatives and the Recruitment of German Expertise

1.1 The Geopolitical Context: Defeating Nazism, Facing the Soviet Union

The conclusion of World War II in Europe did not usher in an era of stable peace but rather marked the transition to a new global confrontation. The defeat of Nazi Germany, formalized by Allied agreements like the Potsdam Agreement of August 1945 which aimed among other things for denazification 1, occurred alongside the rapid disintegration of the wartime alliance between the Western powers and the Soviet Union. Deep ideological divides and competing geopolitical interests quickly led to the division of Europe and the onset of the Cold War.3 This dramatic shift in the international landscape profoundly influenced Allied policies towards occupied Germany and former Axis personnel.

The perceived threat posed by the Soviet Union and the spread of communism became the overriding concern for the United States and its Western allies.4 This fear fueled a strategic competition for resources, influence, and technological superiority. Advanced German military technology, particularly in rocketry, aviation, and potentially chemical and biological weapons, became highly coveted prizes.3 American and British military and intelligence agencies recognized the potential value of harnessing German scientific and technical expertise not only to bolster their own capabilities but, crucially, to deny these assets to the Soviets.3 This competitive dynamic emerged almost immediately, with the US, British, French, and Soviets all actively seeking German specialists who could advance their military and industrial interests.12

This strategic imperative began to overshadow previously stated goals, such as the comprehensive denazification of German society. The urgency of the Cold War provided a powerful rationale for prioritizing the acquisition of German knowledge and personnel above other considerations. The "Soviet threat" was not merely a passive background condition; it became an active justification, deployed both internally within government and sometimes publicly, to legitimize actions that might otherwise have been deemed ethically or politically unacceptable.12 For instance, arguments were made that refusing to utilize invaluable German expertise due to moral objections concerning the individuals' pasts would be strategically foolish, effectively handing an advantage to the Soviet Union.12 This instrumentalization of the Soviet threat created a political climate where programs involving former Nazis became more palatable 3, and the rigorous pursuit of denazification lost momentum, particularly in the Western zones of occupation, as stability and anti-communism took precedence.1 A parallel dynamic can be observed in the US handling of Japanese biological warfare data from Unit 731, where immunity was allegedly granted in exchange for research derived from horrific human experimentation, justified by the perceived need to acquire this knowledge before the Soviets.13 This pattern suggests that perceived national security needs during the Cold War were frequently invoked to sideline prior commitments and ethical norms.

1.2 Operation Paperclip: Securing Scientific and Technical Advantage

Operation Paperclip, initially codenamed Operation Overcast, stands as a prime example of this post-war strategic calculus. It was a secret United States intelligence program initiated in 1945 and continuing until 1959, designed to recruit German and Austrian scientists, engineers, and technicians for government employment in the US.3 Over 1,600 specialists, along with their families, were ultimately brought to America under this program.7

The official objective, established by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff on July 20, 1945, was initially short-term: to leverage German expertise for the ongoing war against Japan and bolster US post-war military capabilities.3 However, even after Japan's surrender in August 1945, the program continued and rapidly evolved.3 The US armed forces and civilian agencies saw a long-term strategic opportunity to seize and exploit Third Reich technologies – particularly advanced aircraft, rockets, and missiles – that were considered superior or competitive.3 The individuals who had designed and developed these technologies were deemed essential for effective technology transfer.3 Thus, what began as a limited advisory project transformed into a program facilitating permanent immigration.3 The estimated value of the acquired knowledge, in terms of patents and industrial processes, has been placed at US$10 billion.9

The execution of Paperclip involved specialized Allied teams, such as the Combined Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee (CIOS), scouring Germany for research facilities, documents, and personnel even before the war ended.4 The discovery of the "Osenberg List," a catalogue of scientists working for the Third Reich found at Bonn University, proved particularly valuable.4 Recruitment and processing were handled by the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), with support from Army Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) agents.4 Recruited personnel were initially brought to locations like Fort Strong in Boston Harbor, Fort Hunt in Virginia, or Mitchel Field in New York for processing and interrogation before being assigned to various military installations.9 Key facilities hosting Paperclip specialists included Fort Bliss, Texas, and White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico (for rocket experimentation), and later Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, which became a major center for missile development.3 Eventually, many specialists were integrated into civilian agencies like NASA or employed by private industry.3 This recruitment drive was part of a competitive landscape, as the British, French, and Soviets were simultaneously pursuing similar efforts to secure German technical expertise.12

The program's evolution from the short-term goals of "Overcast" to the long-term immigration facilitated by "Paperclip," even after the original justification (war against Japan) disappeared, highlights a significant aspect of institutional behavior. It demonstrates an adaptability driven by perceived strategic necessity, where the initial, limited mandate was readily expanded to capitalize on a larger opportunity – securing a technological edge in the nascent Cold War.3 This was not an accidental drift but a deliberate adaptation by military and intelligence bodies like the JIOA and the War Department, reflecting a pragmatic approach that prioritized potential strategic gains over adherence to the original program parameters. Such programs, once initiated, can develop their own momentum and rationales, shaped by bureaucratic interests and evolving geopolitical calculations, potentially moving far beyond their initial scope and justification.

1.3 The Gehlen Organization: Leveraging Intelligence Assets Against the East

Concurrent with the efforts to secure scientific talent, the United States also sought to acquire intelligence assets useful in the emerging conflict with the Soviet Union. This led to the formation of the Gehlen Organization, an entity that would become a cornerstone of early Western intelligence operations against the Eastern Bloc. Its founder, Reinhard Gehlen, was a Wehrmacht Major General who had headed the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO), Nazi Germany's military intelligence service focused on the Eastern Front.19

Anticipating Germany's defeat and recognizing the value of his organization's intelligence holdings on the Soviet Union, Gehlen arranged for the microfilming and burial of FHO archives in the Austrian Alps in early 1945.20 On May 22, 1945, he and his senior aides surrendered to a US Army Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) team.20 Recognizing the significant gap in its own intelligence capabilities regarding its former Soviet ally, the US military intelligence (G-2) saw an opportunity.20 Gehlen successfully negotiated an agreement allowing him to reconstitute his intelligence network under American sponsorship, operating despite post-war denazification policies.20

Established in June 1946 19, the Gehlen Organization, or "the Org," had the primary purpose of gathering political, economic, and technical intelligence on the Soviet Union and its satellite states for the benefit of the United States, particularly the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) after 1947.19 The Org was composed largely of former members of the Wehrmacht's intelligence apparatus, but also included personnel from the SS (Schutzstaffel) and SD (Sicherheitsdienst), the Nazi party's intelligence service.19 Hundreds of former German army and SS officers were reportedly released from internment camps to staff the organization.20 Headquartered initially near Frankfurt and later in Pullach, near Munich, under the cover name "South German Industrial Development Organization," the Org grew significantly, employing thousands of intelligence specialists and undercover agents (V-men) operating across the Soviet bloc.20 The CIA provided funding and material support, including vehicles and aircraft, while the Org supplied the manpower and operational network.19

The Gehlen Organization conducted a range of operations, including systematically interviewing German prisoners of war returning from Soviet captivity, which provided invaluable, up-to-date information on conditions inside the USSR.19 It ran espionage networks, conducted counter-espionage activities against dissident German groups (Operation Rusty) 19, and attempted infiltration and destabilization efforts in Eastern Europe, such as Operation Sunrise and the ill-fated WIN operation in Poland (which turned out to be a Soviet deception).20 For many years, the Org was considered the CIA's principal source of on-the-ground intelligence within the Soviet sphere.19 However, its intelligence was not always accurate and sometimes contributed to misperceptions, such as the "missile gap" narrative.20 In April 1956, the Gehlen Organization was formally transferred to the sovereignty of the West German government, forming the nucleus of the new Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the Federal Intelligence Service. Reinhard Gehlen served as the BND's first president until his retirement in 1968.19

The reliance on the Gehlen Organization exemplifies the complex trade-offs inherent in utilizing intelligence structures from a defeated authoritarian regime. While the Org undoubtedly provided the US with crucial intelligence during the early Cold War when American capabilities were limited 19, its composition created significant and inherent risks. Staffing the organization with personnel deeply embedded in the Nazi system, including former SS and SD members 19, meant employing individuals whose loyalties could be questionable, who might hold extremist ideologies, or who could be vulnerable to compromise. Indeed, the Org suffered from significant Soviet penetration, with key insiders like Heinz Felfe, Hans Clemens, and Erwin Tiebel – all former Nazis recruited by Soviet intelligence – betraying operations and agents for years before their discovery in 1961.19 This demonstrates that the very method chosen to gain an intelligence advantage – leveraging Gehlen's existing network – carried within it the seeds of its own compromise. Furthermore, the association with numerous individuals implicated in Nazi crimes created long-term political and ethical liabilities for both the United States and the nascent West German state.19 The decision to utilize the Gehlen Org was thus a calculated risk, balancing the immediate need for intelligence against the potential for counterintelligence failures and enduring moral and political repercussions.

1.4 Moral Compromises: Ethical Debates and the Whitewashing of Pasts

The recruitment of German scientists through Operation Paperclip and the establishment of the Gehlen Organization were fraught with profound ethical controversies from their inception. Both initiatives involved the active utilization, protection, and integration of individuals who had served, often in significant capacities, a regime responsible for unprecedented atrocities, including the Holocaust and widespread war crimes.3 Many of the recruited personnel were not merely nominal participants but had been members of the Nazi Party or the SS, and some were directly implicated in crimes such as the use of slave labor or human experimentation.3

A key element facilitating these programs was the deliberate "whitewashing" of participants' records. Despite an official directive from President Harry Truman forbidding the recruitment of confirmed Nazi Party members or active Nazi supporters for Paperclip 4, officials within the JIOA and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the CIA's predecessor, systematically circumvented this order.4 Incriminating evidence regarding Nazi affiliations and potential involvement in war crimes was actively eliminated, altered, or sanitized from personnel files.4 This process was sometimes quite literal, with paperclips reportedly attached to the files of desired scientists to expedite their selection and immigration, lending the operation its eventual name.5 A deliberate propaganda campaign was even undertaken by the US government to obscure the backgrounds of these scientists, involving requests for intelligence officers to rewrite dossiers and assertions from military leaders that history would need to be rewritten to accommodate the strategic necessity.25

The primary justification offered for these ethical compromises was national security in the context of the escalating Cold War.3 The prevailing argument was that the scientific knowledge and intelligence expertise possessed by these individuals were indispensable for maintaining a technological and strategic advantage over the Soviet Union.3 Denying these assets to the Soviets was considered as important as acquiring them for the US.3 Proponents contended that these pragmatic considerations outweighed the moral objections related to the individuals' past actions.10

However, these decisions were not made without internal dissent. Some within the US government, particularly in the State Department, raised concerns about the morality and potential security risks of bringing former Nazis into sensitive programs.12 The leniency afforded to Paperclip recruits stood in contrast to the stricter denazification policies being applied, at least initially, elsewhere in the US-occupied zone of Germany.12 This practice of prioritizing perceived national interest over accountability for war crimes was not unique to German personnel. The handling of Japan's Unit 731, where researchers involved in horrific human experiments were reportedly granted immunity by the US in exchange for their data on biological warfare, suggests a broader pattern during the early Cold War.13

The systematic nature of the "whitewashing" associated with Operation Paperclip indicates that circumventing ethical directives was not merely the action of isolated individuals but became a normalized, albeit covert, bureaucratic procedure within certain intelligence and military agencies.4 When strategic goals, particularly those related to the Cold War, were deemed sufficiently important, established protocols and ethical guidelines could be bypassed through organized efforts involving multiple levels of command. This points to the potential for a significant disconnect between a nation's publicly stated values and policies and the clandestine operational practices of its security apparatus, particularly during periods of heightened geopolitical tension.

Furthermore, the decisions to grant impunity or minimize the pasts of individuals implicated in atrocities carry consequences that extend far beyond the immediate post-war period. Shielding Paperclip scientists 3, Gehlen Organization members 19, and potentially Unit 731 researchers 13 from full accountability prioritized short-term strategic gains over the principles of justice. This pattern, where utility effectively trumped culpability, established historical precedents. Such actions could inadvertently signal to future actors that involvement in severe human rights violations might be overlooked if the individuals possess sufficiently valuable skills or information. This potential long shadow of impunity risks undermining the foundations of international law and transitional justice efforts, weakening the global commitment to holding perpetrators of mass atrocities accountable, regardless of their perceived strategic value.

Section 2: Assessing Post-War Influence: Individuals, Ideologies, and the "Infiltration" Question

Evaluating the impact of the individuals recruited through programs like Operation Paperclip and the Gehlen Organization requires examining their specific contributions, the broader context of denazification in Germany, and the evidence for any persistent ideological influence or network activity within Western institutions.

2.1 Notable Figures: Contributions and Controversies

Several individuals brought to the West after WWII achieved significant prominence, their careers embodying both remarkable technical achievements and profound ethical dilemmas.

Wernher von Braun is arguably the most famous and controversial figure associated with Operation Paperclip.3 As the technical director of the Nazi V-2 rocket program at Peenemünde 7, he oversaw the development of the world's first long-range ballistic missile, a weapon used against Allied cities, killing thousands.26 Critically, the production of the V-2, particularly in its later stages at the underground Mittelwerk factory near Nordhausen, relied heavily on slave labor from the adjacent Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, where tens of thousands of prisoners perished under horrific conditions.7 Von Braun was a member of the Nazi Party (joining in 1937) and the Allgemeine-SS (joining in 1940, reaching the rank of Major by 1943).3 While he and his defenders often portrayed his affiliations as nominal, opportunistic, or coerced to protect his life's work in rocketry 15, evidence, including his visits to Mittelwerk and documented involvement in discussions about prisoner labor 8, points towards a deeper level of complicity. After surrendering to the Americans in 1945 9, von Braun and key members of his team were brought to the US via Paperclip.3 He became a central figure in the US Army's ballistic missile program at Redstone Arsenal 3 and later transferred to NASA, where he served as director of the Marshall Space Flight Center and was the chief architect of the Saturn V rocket, the launch vehicle for the Apollo Moon missions.3 His legacy remains deeply contested, balancing his undeniable contributions to space exploration against his service to the Nazi regime and his connection to the crimes committed in the V-2 program.5

Reinhard Gehlen, as detailed previously, transitioned from leading Nazi Germany's Eastern Front intelligence (FHO) to heading the US-sponsored Gehlen Organization.20 This organization, staffed heavily with former Wehrmacht, SS, and SD personnel 19, served as a primary intelligence source on the Soviet Bloc for the CIA for nearly a decade.19 The employment of individuals with backgrounds in Nazi intelligence agencies, including known war criminals 19, was a source of ongoing controversy and vulnerability, highlighted by the successful penetration of the Org by Soviet intelligence agents recruited from its ranks.19 Gehlen's subsequent appointment as the first head of West Germany's BND cemented the continuity of personnel from the Third Reich's intelligence apparatus into the post-war Federal Republic's security structure.19

Beyond these two prominent figures, Operation Paperclip and related programs brought numerous other specialists with problematic pasts to the West. Kurt Blome, former Deputy Surgeon General of the Third Reich and head of Nazi biological warfare research involving experiments on prisoners, was acquitted at the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial and subsequently recruited to work on US biological warfare programs.7 Arthur Rudolph, production manager at the Mittelwerk V-2 factory utilizing slave labor, became a key figure in the US Pershing and Saturn missile programs, receiving NASA's Distinguished Service Medal before evidence of his past led him to renounce his US citizenship in 1984 to avoid trial.5 Hubertus Strughold, known as the "Father of Space Medicine" in the US for his contributions to understanding the physiological requirements for spaceflight, was later linked to human experiments involving extreme cold and low oxygen conducted on concentration camp prisoners during the Nazi era, leading to the removal of his name from a NASA award.5 Others included Georg Rickhey, a former official at the Nordhausen V-2 factory who was brought over in 1946 but returned to Germany in 1947 to face trial for war crimes (he was acquitted) 16, and Walter Schreiber, implicated in medical experiments.16 The range of expertise sought was broad, encompassing rocketry, aerospace engineering, electronics, materials science, medicine, physics, and chemistry.17

The careers of these individuals illustrate a recurring pattern: highly specialized, strategically valuable expertise often served as a shield against full accountability for past actions associated with the Nazi regime. The pressing needs of the US government for advanced scientific knowledge (von Braun, Rudolph, Strughold) 3, intelligence capabilities (Gehlen) 20, or specific technical skills (Blome) 7 created a dynamic where their contributions were actively sought and amplified, while their problematic histories were systematically minimized, obscured, or excused.4 This created a symbiotic relationship: the specialists gained protection, prestigious new careers, and avoidance of prosecution, while the United States secured significant technological and intelligence advantages in the Cold War. This demonstrates how perceived strategic necessity can construct pathways to impunity, allowing individuals implicated in serious crimes to escape justice due to the perceived value of their skills.

2.2 Denazification: Intentions vs. Outcomes in Occupied Germany

The integration of individuals like von Braun and Gehlen into Western structures occurred against the backdrop of Allied denazification efforts in occupied Germany and Austria. Denazification was the ambitious Allied initiative launched after WWII to purge German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of National Socialist ideology, influence, and personnel.1 Initial measures included repealing Nazi laws, removing Nazi symbols from public life, banning Nazi organizations, culling Nazi literature from libraries, and prosecuting major war criminals at the Nuremberg Trials.1 A key tool was the mandatory questionnaire, the Fragebogen, which millions of Germans had to complete, detailing their affiliations with Nazi organizations and their wartime activities.1 Based on these questionnaires and further investigations, individuals were classified into categories ranging from "Major Offenders" to "Followers" and "Exonerated," with corresponding sanctions.34 Special tribunals, known as Spruchkammern, often staffed by Germans vetted by the Allies, were established to adjudicate cases.1 Initially, particularly in the US zone, the process was pursued with considerable zeal, involving the "automatic arrest" and internment of hundreds of thousands of former Nazi functionaries and members.1

However, the implementation and effectiveness of denazification proved highly problematic and ultimately limited.32 A major challenge was inconsistency; the four occupying powers (US, UK, France, Soviet Union) lacked a unified approach, leading to significant variations in procedure and rigor across the different zones.1 The sheer scale of the task – processing millions of questionnaires and cases – overwhelmed the available Allied and later German administrative capacity, leading to massive backlogs and delays.1

Crucially, the escalating Cold War fundamentally altered Allied priorities.1 The US and Britain, in particular, grew less interested in pursuing thorough denazification as concerns about Soviet expansion, economic recovery, and maintaining stability in West Germany took precedence.1 Responsibility for denazification was transferred to German authorities relatively early (1946 in the Western zones) 1, who faced political pressure and practical difficulties. Proving individual guilt was often hard, and the system became reliant on personal testimonials (Persilscheine), often provided by friends or neighbors, which contributed to lenient outcomes.33 Consequently, the vast majority of individuals processed were classified in the lower categories of "Follower" or "Exonerated," facing minimal sanctions.33 Many former Nazis, especially those not in the top leadership or those possessing needed skills (like the Paperclip scientists exempted from the process 1), avoided serious consequences and were eventually reintegrated into West German society, administration, and industry.32 West German amnesty laws passed in 1949 and 1954 further solidified this trend.38

The legacy of denazification is therefore deeply ambiguous. While it failed in its goal of comprehensively purging German society and holding most perpetrators accountable 33, it was not without impact. The process did disrupt the careers and influence of many former Nazis, introduced the principle of individual accountability for political actions into German public life 38, and arguably played a role in the long-term failure of overtly neo-Nazi political parties to gain a significant foothold in post-war Germany.33 Some scholars also argue that the Fragebogen process, despite its flaws and the often self-serving nature of the responses it elicited (with many constructing narratives of personal victimhood 37), forced a widespread, if often superficial, confrontation with the Nazi past at an individual level.37

The premature curtailment and incomplete implementation of denazification, largely driven by the pragmatic calculations of the Cold War and immense logistical hurdles, carried significant unintended consequences beyond the simple reintegration of personnel. By prioritizing stability and anti-communism over a thorough reckoning, the Western Allies, and subsequently the West German authorities, allowed many individuals implicated in the Nazi regime to return to positions of influence.33 This failure not only raised questions of justice but also potentially contributed to a prolonged period of societal silence or distorted collective memory regarding the Nazi era within significant parts of West German society.2 The emphasis shifted from accountability towards integration and rehabilitation 1, which, while perhaps necessary for rebuilding, may have hindered a deeper, more comprehensive societal confrontation with the crimes and ideology of the Third Reich. This suggests that transitional justice processes, when cut short or implemented superficially due to overriding political or strategic concerns, can have lasting negative effects on a society's ability to fully grapple with and learn from its past.

2.3 Evaluating the Persistence of Networks and Ideology: Historical Evidence

Assessing the extent to which cohesive Nazi networks or ideologies persisted and exerted influence within Western governments and societies after WWII, particularly as a direct result of programs like Paperclip or the Gehlen Organization, is complex. Definitive proof of organized, ideologically driven underground networks aiming for subversion is elusive in the available public record. However, evidence does point towards significant continuity of personnel and the potential for lingering influence.

The Gehlen Organization provides the clearest example of network continuity. It was explicitly built upon the structure and personnel of the Nazi FHO, employing hundreds, potentially thousands, of former Wehrmacht intelligence officers, SS members, and SD agents.19 This group inherently constituted a network of individuals with shared wartime experiences and, potentially, shared worldviews, operating first under US control and then forming the core of the West German BND.19 Reports from the time even described the Org's headquarters as a place where "Himmler's elite were having happy reunion ceremonies".22 The very existence and later institutionalization of this organization demonstrate a direct transfer of personnel networks from the Third Reich into the Cold War security apparatus of the West.

Furthermore, the incomplete nature of denazification across West Germany allowed numerous individuals with Nazi backgrounds to return to influential positions not just in intelligence, but also in public administration, the judiciary, and industry.33 Studies have noted a marked difference between West Germany, where such continuity was common, and East Germany, where denazification, driven by different political motives, was initially pursued more forcefully, leading to a more significant break with the past personnel structures, at least formally.33

Operation Paperclip personnel, while primarily valued for their technical skills, also brought their personal histories and potential ideological baggage into highly sensitive US military and space programs.3 Some sources suggest that a number of these recruits were not merely nominal party members but held strong beliefs in Nazi ideology.27 While their primary influence was technical, their presence in these environments represents another form of personnel continuity. Additionally, narratives surrounding post-war escape networks for Nazis, such as the "ratlines" or organizations like ODESSA (mentioned in connection with Gehlen, though its historical significance is debated 22), suggest the existence of support structures, potentially aided or tolerated by elements within Western institutions or intelligence services.22 The emergence and persistence of explicit neo-Nazi groups in the United States from the 1950s onwards (e.g., American Nazi Party, National Alliance, National Socialist Movement 40) also clearly indicates the survival and adaptation of Nazi ideology itself, although these groups are not directly linked in the sources to an infiltration strategy via Paperclip or the Gehlen Org.

However, several factors nuance the interpretation of this continuity. The documented primary motivation for Paperclip and the Gehlen Org was strategic gain in the Cold War, not ideological propagation. The influence exerted by Paperclip scientists appears overwhelmingly technical rather than political or ideological. The Gehlen Organization, despite its origins, proved vulnerable to penetration by Soviet intelligence 19, suggesting its internal ideological cohesion and operational security were far from absolute. Moreover, denazification, despite its significant flaws, did contribute to an environment in both East and West Germany where overtly Nazi political parties failed to achieve lasting mainstream success.33

Therefore, while the evidence strongly confirms a significant continuity of personnel with Nazi backgrounds into key Western scientific and intelligence structures 1, facilitated by Cold War pragmatism and flawed denazification, the evidence for these individuals operating as part of a coordinated, ideologically motivated conspiracy to infiltrate and subvert Western governments from within through these specific programs is considerably weaker based on the provided materials. The narrative consistently points towards the exploitation of skills and knowledge for strategic advantage.3 While the presence of these individuals was ethically reprehensible and created undeniable risks, including counterintelligence vulnerabilities and the potential for perpetuating certain biases, interpreting this solely through the lens of deliberate ideological "infiltration" may misrepresent the primary historical drivers documented in these sources.

2.4 Addressing the "Infiltration" Narrative: Strategic Recruitment vs. Covert Subversion

Synthesizing the findings on the post-war context, the specific programs, and the subsequent influence and denazification process allows for a direct assessment of the user's query regarding US "infiltration" of Germany and Europe with Nazis.

The historical record, as reflected in the provided sources, consistently points to the primary motivation behind programs like Operation Paperclip and the establishment of the Gehlen Organization as strategic advantage in the Cold War.3 The goal was to acquire advanced German technology, scientific expertise, and intelligence capabilities concerning the Soviet Union before the Soviets could, thereby strengthening the US position in the emerging bipolar conflict.

The undeniable consequence of pursuing these strategic goals through these particular means was the recruitment, relocation, protection, and integration of a significant number of individuals with Nazi pasts – including party members, SS officers, and persons implicated in war crimes – into sensitive positions within the US military-industrial complex, intelligence agencies, and, via the Gehlen Org, the nascent West German security structure.3 This outcome was facilitated by deliberate actions to obscure or "whitewash" their histories.4

However, distinguishing between motive and outcome is crucial. While the presence of these individuals was deeply problematic ethically and created tangible risks (such as the Soviet penetration of the Gehlen Org 19 or the simple moral hazard of rewarding individuals associated with atrocities), the available evidence does not substantiate the claim that the primary purpose of these US-led programs was to ideologically infiltrate Germany and Europe with Nazi sympathizers to achieve some unstated political goal. The documented objectives and the overwhelming contextual evidence point towards the pragmatic, albeit ethically compromised, exploitation of skills and knowledge for American strategic benefit in the Cold War. The Gehlen Organization, for instance, was explicitly directed against the Soviet Bloc, not as a tool for internal subversion of the West.19

Therefore, the "infiltration" narrative, while perhaps capturing the legitimate unease and moral outrage surrounding the presence of these individuals in positions of influence, likely misinterprets the dominant strategic rationale driving these specific US actions. The historical reality appears more complex: a confluence of perceived urgent national security needs in the face of the Soviet threat, the availability of unique German expertise, and a willingness within certain US agencies to make significant ethical compromises and bypass stated policies to achieve strategic objectives. The focus was on harnessing capabilities, not intentionally seeding Nazi ideology within Western institutions via these programs.

Section 3: The Contemporary Landscape: Global Far-Right Networks

Decades after the end of World War II and the Cold War, democratic societies face new challenges from extremist ideologies, particularly from a resurgent and increasingly interconnected global far-right. Understanding the nature of these contemporary movements is essential for drawing relevant comparisons to the past and formulating effective countermeasures.

3.1 Ideological Foundations: Nativism, Authoritarianism, and Anti-Democracy

The contemporary far-right is not a monolithic entity but rather a diverse and heterogeneous milieu.41 It encompasses a spectrum of actors, including formal political parties contesting elections, social movements mobilizing public opinion through extra-parliamentary means, and a constellation of subcultural groups and online communities.41 Despite this diversity, these groups are generally united by a core set of ideological tenets.

Central to the far-right worldview are nativism and authoritarianism.42 Nativism manifests as the belief that the interests of the established, "native" inhabitants of a nation should be prioritized over those of immigrants or minority groups.42 Contemporary far-right discourse often frames this nativism in terms of cultural incompatibility or the defense of a specific "civilization" or "identity," rather than relying solely on older theories of biological racism – a concept sometimes termed "ethnopluralism".41 This shift towards cultural arguments is often seen as a strategy to gain broader legitimacy and appeal.41 Authoritarianism involves a preference for strong, centralized state power, a rejection of liberal pluralism, and often a belief in natural hierarchies and inequalities between groups.42

Consequently, a strong undercurrent of anti-democracy pervades much of the far-right.42 This can range from criticism of specific democratic institutions and norms (perceived as weak, corrupt, or biased against the "true" nation) to outright rejection of liberal democracy in favor of more authoritarian models. Specific themes commonly found within this ideological framework include: white identity politics, white supremacy, or white nationalism 40; staunch anti-immigration sentiment 43; antisemitism 45; Islamophobia and anti-Muslim prejudice 43; hostility towards LGBTQ+ rights 47; extreme misogyny 51; and a pronounced reliance on conspiracy theories, such as the "Great Replacement" narrative (claiming elites are intentionally replacing white populations with immigrants), QAnon, or unfounded claims of widespread election fraud.45 In its more extreme forms, the ideology may openly glorify violence, advocate for civil unrest or societal collapse (accelerationism), or promote narratives anticipating a future race war or "Day X" scenario.44

3.2 Modern Mobilization: Digital Ecosystems and Real-World Action

The methods used by contemporary far-right actors to mobilize support, spread ideology, and coordinate actions are heavily influenced by modern technology, particularly the internet and social media platforms.41 These digital tools offer low-cost, rapid communication channels that allow groups to bypass traditional media gatekeepers and disseminate messages, including radical ideologies and disinformation, that might otherwise be filtered out.42

Online platforms serve multiple functions: they host propaganda, facilitate recruitment, enable fundraising, allow for the planning and coordination of activities (including training), and foster the creation of like-minded communities, often spanning national borders.41 Specific tactics include the use of viral memes and coded language to spread ideas (characteristic of the "alt-right" 48), the establishment of dedicated forums and channels on both mainstream platforms and alternative "alt-tech" sites (which can function as radicalization echo chambers 42), and the exploitation of algorithms to amplify content. In some extreme cases, perpetrators have live-streamed terrorist attacks online.54

Crucially, this online activity is deeply intertwined with real-world action, creating a hybrid mobilization model.41 Digital platforms are used to organize offline events, such as street protests, demonstrations, and rallies.41 Far-right groups increasingly participate in public demonstrations, sometimes appearing alongside more mainstream conservative movements, particularly at events focused on issues like anti-LGBTQ+ or anti-abortion activism.47 Online rhetoric can translate into offline harassment and intimidation campaigns targeting individuals or groups 52, or attempts to influence the political process by running for office or lobbying policymakers.50 In more extreme segments, online networks facilitate paramilitary training and recruitment for violent action.54 This connection between online radicalization and offline violence is evident in numerous terrorist attacks inspired by far-right ideologies.45 The strategy of "leaderless resistance," encouraging lone actors or small cells to carry out attacks inspired by online propaganda, further complicates counter-terrorism efforts.54

Simultaneously, far-right actors and the issues they champion (such as migration and cultural identity) have gained increased visibility and resonance in mainstream public discourse in recent years.43 This "mainstreaming" is partly fueled by media attention and, in some countries, the institutional access gained by far-right political parties achieving electoral success (like the Alternative for Germany, AfD).43 This dynamic illustrates the complex interplay between online organizing, offline action, and broader societal and political trends, where digital platforms serve as crucial infrastructure connecting and amplifying far-right activities across both virtual and physical spaces. Addressing this phenomenon requires strategies that recognize and tackle this hybridity, targeting both online networks and their real-world manifestations.

3.3 Transnational Collaboration and Shared Narratives

A defining characteristic of the contemporary far-right landscape is the significant increase in international networking and collaboration.41 Security agencies and researchers alike have noted that right-wing extremists are connecting across borders and even continents more than ever before.54 Organizations like Europol and the Counter Extremism Project (CEP) have highlighted the emergence of transnational movements and the influence of global personalities and ideologies.54

This transnationalism is underpinned by a shift in ideology for many adherents. While traditional nationalism remains a component, many contemporary far-right extremists increasingly frame their struggle not in narrow national terms, but as part of a global conflict against perceived global enemies.54 Concepts like "globalism," multiculturalism, liberal democracy, and shadowy "elites" are cast as transnational threats requiring a coordinated international response from those who seek to defend white identity, traditional values, or national sovereignty.54 Potent transnational narratives, such as the "Great Replacement" conspiracy theory, resonate across different national contexts, providing a shared framework of grievance and threat perception.53

These transnational connections manifest in various ways. Shared ideologies, key texts (like James Mason's Siege), and influential figures inspire and link groups globally.54 Online platforms are critical hubs for building these international networks, allowing for easy communication and exchange of ideas between individuals and groups in different countries.41 Collaboration also occurs offline through physical meetings, international conferences, music festivals, combat sports events, and joint training exercises.44 Participation in foreign conflicts, such as the war in Ukraine, has also provided opportunities for far-right extremists from different countries to connect and gain combat experience.54 Specific organizations, like the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), have been identified as hubs facilitating international connections and potentially providing training.54 Furthermore, the actions and rhetoric of prominent far-right groups or figures in one country, particularly the United States, can influence and inspire groups elsewhere.54 European far-right political parties also engage in forms of cooperation and mutual learning.59 Monitoring organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) 45 and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) 52 track these domestic and international hate groups and their activities. There are also concerns about state actors, notably Russia, potentially seeking to exploit and amplify far-right movements in Western democracies as a means of sowing division and undermining political stability.57

This phenomenon reflects a "globalization of grievance," where local discontents – whether economic hardship, social anxieties about immigration, or cultural insecurities 43 – are increasingly interpreted and articulated through overarching, internationally resonant narratives propagated by the far-right.53 Digital communication technologies act as powerful accelerators for this process, enabling the rapid dissemination of these globalized narratives and facilitating connections between individuals and groups who come to see themselves as part of a common, borderless struggle. This implies that purely nation-centric approaches to understanding and countering far-right extremism may prove insufficient. Effective strategies likely require international cooperation and a keen awareness of the globalized ideologies and narratives that are being leveraged to mobilize support across diverse local contexts.

Section 4: Historical Echoes: Connecting Post-War Realities to Present Dangers

Drawing parallels between the post-WWII recruitment of individuals with Nazi pasts and the contemporary landscape of global far-right networks requires careful consideration of both similarities and crucial differences. While direct equivalence is inappropriate, examining the historical precedents can offer valuable perspectives on current challenges.

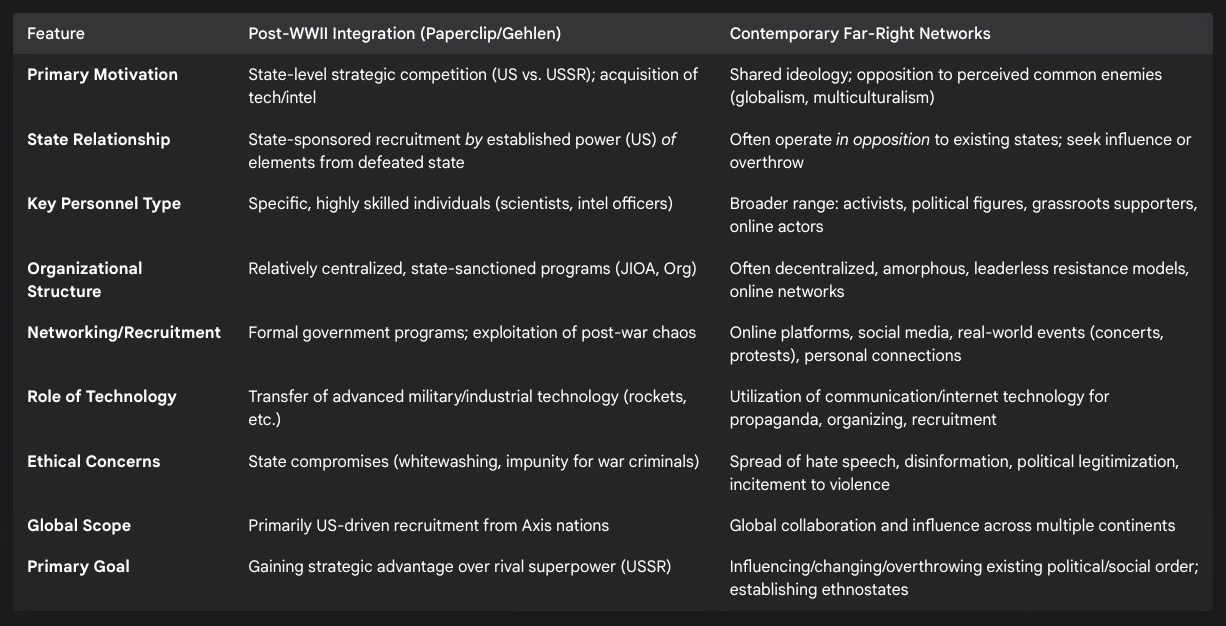

4.1 Analogies and Divergences: Comparing Post-WWII Integration and Modern Far-Right Networks

The analogy requested by the user, comparing the post-war situation with present dangers, reveals both resonant echoes and significant distinctions:

Points of Analogy: Both periods demonstrate the transnational dimension of actors and ideologies, whether through state-sponsored relocation 9 or global online collaboration.54 Both saw the exploitation of crises – post-war chaos and the Cold War then 3, economic, migration, and political crises now 51 – to advance specific agendas or justify actions. Technology played a key role, albeit differently: the transfer of physical technologies then 3, the leveraging of communication technologies now.42 Both contexts reveal ethical compromises by powerful actors, whether states overlooking past crimes for strategic gain 4 or modern political figures potentially legitimizing extremist narratives.53 Finally, both eras show the persistence and adaptability of extremist ideologies, from Nazism to neo-Nazism 40 and today's diverse far-right currents.41

Points of Divergence: The relationship with the state is fundamentally different: post-WWII involved established states recruiting elements from a defeated enemy 9, whereas modern networks often oppose the states they operate within.54 The primary motivations differ: state-centric strategic competition then 3, versus ideologically driven opposition to perceived global trends now.54 The personnel involved are different: specific experts then 17, a broader activist base now.41 Organizational structures also contrast: formal programs then 16, versus more decentralized, networked structures now.54

This comparison highlights that while historical parallels exist, particularly regarding the transnational nature of threats and the ethical challenges they pose, the contemporary far-right operates within a distinct context with different motivations, structures, and relationships to state power compared to the specific post-WWII programs examined.

4.2 The Continuity of Extremist Appeals and Tactics

Despite the differences in context, certain underlying appeals and tactics employed by extremist movements demonstrate a degree of continuity. The scapegoating of minority groups – whether Jews and other perceived enemies in Nazi ideology, or immigrants, Muslims, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other minorities targeted by contemporary far-right groups – remains a core tactic for mobilizing resentment and consolidating group identity. Exploiting national anxieties, economic grievances, or feelings of cultural displacement is another common thread, used to build a narrative of crisis that justifies radical solutions.53

The use of propaganda and disinformation, tailored to the communication technologies of the era, is also a constant. While the Nazis utilized radio and film, modern extremists masterfully exploit the internet and social media.42 Appeals to a romanticized or threatened national identity, often defined in exclusionary ethnic or cultural terms, are central to both historical Nazism and contemporary far-right nationalism. A fundamental challenge to democratic institutions and norms is another shared characteristic, stemming from a belief in authoritarianism or the illegitimacy of the existing liberal order.42 Finally, the potential for, and sometimes explicit advocacy of, violence as a political tool links historical fascist movements with the more extreme elements of the contemporary far-right.54

The adaptability of the core ideology is also notable. Overt Nazism gave way to various forms of neo-Nazism after the war.40 Today's far-right often emphasizes cultural nativism or relies heavily on conspiracy theories, adapting its language and focus to resonate with contemporary concerns while often retaining underlying themes of exclusion, hierarchy, and anti-democratic sentiment.41 This demonstrates the enduring nature of certain extremist appeals and their capacity to morph and re-emerge in different historical contexts.

Section 5: Defending Democracy: Lessons Learned and Future Strategies

Understanding the historical handling of Nazi-affiliated personnel and the nature of contemporary far-right threats provides a basis for considering how non-authoritarian societies can protect themselves. This involves critically assessing past responses and synthesizing current expert recommendations for building democratic resilience.

5.1 Historical Responses to Extremism: A Critical Assessment

The Allied denazification program in post-war Germany offers significant, albeit complex, lessons. Its mixed results underscore the difficulty of eradicating entrenched ideologies and holding perpetrators accountable on a mass scale.32 The process suffered from inconsistency across occupation zones, bureaucratic overload, and, most critically, a decline in political will driven by the Cold War.1 The early handover of responsibility to German authorities, who faced their own political pressures and capacity limitations, further diluted the effort.1 The lesson here is that such processes require sustained commitment, consistency, adequate resources, and insulation from short-term political expediency to be truly effective. As observed, incomplete or prematurely terminated processes can have negative long-term consequences for societal memory and reconciliation.2

Other historical responses to extremism within democracies also offer cautionary tales. Actions such as the suspension of habeas corpus during the US Civil War 56 or violent state responses to protest, like the Kent State shootings 56, highlight the danger of employing anti-democratic means to counter perceived threats, potentially undermining the very values being defended. Conversely, efforts focused solely on legal proscription or reactive security measures may fail to address the underlying societal conditions that allow extremism to flourish. The long struggle against groups like the Ku Klux Klan 40 or the emergence of neo-Nazi groups despite post-war efforts 40 illustrate the persistence of extremist ideologies. Research suggests that while democratic openness can be exploited by extremists 64, it also offers advantages by allowing grievances to be addressed peacefully and making it harder for violent fringe groups to gain traction compared to authoritarian regimes where dissent is suppressed.64 The key challenge lies in finding responses that are effective against genuine threats without eroding fundamental democratic rights and principles.

5.2 Expert Recommendations for Countering Contemporary Extremism

Contemporary analyses and expert recommendations for countering far-right and other forms of violent extremism converge on a multi-faceted approach, recognizing that no single "silver bullet" exists.65 Key elements include:

Whole-of-Society Approach: Effective strategies require collaboration between government agencies (intelligence, law enforcement, social services, education), civil society organizations, local communities, educators, families, and the private sector, particularly technology companies.51

Prevention (PVE - Preventing Violent Extremism): This involves proactive measures to address the root causes and "drivers" of extremism, such as socio-economic grievances, political marginalization, and identity conflicts.44 It includes building community resilience, promoting inclusive development, fostering tolerance and respect for diversity, supporting education initiatives (including media literacy), developing credible counter-narratives to extremist propaganda, and raising public awareness.44

Intervention: Programs designed to identify individuals at risk of radicalization and divert them from pathways to violence before criminal activity occurs.66 These "off-ramps" can involve tailored support such as psychosocial counseling, mentoring (potentially involving former extremists), theological or ideological debate, and assistance with education or employment.44 Family counseling may also play a role.68

Law Enforcement and Security Measures: While prevention is key, robust security responses remain necessary. This includes dismantling extremist networks, disrupting their financial activities (targeting revenue streams from merchandise, music, events 60), seizing illegal weapons and preventing access to arms for known extremists 60, prosecuting illegal activities (including incitement, hate crimes, and terrorist acts), and enhancing intelligence gathering specifically focused on far-right and other extremist groups.55 Consideration should also be given to legal frameworks for addressing harmful groups that operate below the threshold of proscription but still propagate dangerous ideologies.51

Addressing the Online Dimension: Countering extremism requires specific strategies for the digital space, including fact-checking and debunking disinformation 65, clear labeling of problematic content 65, consistent enforcement of platform terms of service against hate speech and incitement, removal of inauthentic accounts and coordinated networks 65, enhancing cybersecurity for elections and democratic institutions 65, and investigating the role of algorithms in potentially amplifying extremist content.42

Political Leadership and Government Conduct: Mainstream political leaders have a crucial role in unequivocally condemning extremism and violence, refusing to legitimize extremist narratives or groups, and upholding democratic norms.51 Governments should establish clear principles for engagement to avoid inadvertently providing platforms or funding to extremist actors.69

Research and Analysis: Continuous research is needed to better understand the evolving nature of extremist threats, the drivers of radicalization, and the effectiveness of different counter-measures.51 This includes improving data collection and establishing dedicated analytical capabilities or centers of excellence.51

5.3 Fostering Democratic Resilience: Proactive and Societal Approaches

Beyond specific counter-extremism programs, a broader goal is to enhance democratic resilience – the capacity of democratic societies, institutions, and values to withstand, adapt to, and recover from various shocks and stresses, including the challenge posed by extremism.51 This requires proactive, long-term investment in the foundations of democratic life, moving beyond purely reactive security measures.

Key elements of fostering resilience include:

Strengthening Democratic Institutions and Trust: Ensuring government transparency, accountability, and responsiveness can help counter narratives of elite corruption or system failure that extremists exploit. Rebuilding public trust in institutions is paramount.51

Promoting Social Cohesion and Inclusion: Actively fostering inclusive societies that value diversity and provide equal opportunities for all members can reduce the appeal of exclusionary ideologies.51 Addressing discrimination and promoting intergroup dialogue are vital components.66

Supporting a Healthy Information Ecosystem: Investing in independent, high-quality journalism, particularly at the local level, provides citizens with reliable information to counter disinformation.65 Promoting media literacy education equips citizens to critically evaluate information sources.65

Investing in Education: Civic education that promotes democratic values, critical thinking, and an accurate understanding of history (including difficult periods) is fundamental.46

Addressing Socio-Economic Grievances: Tackling underlying issues like economic inequality, lack of opportunity, and regional disparities can reduce the pool of grievances that extremist groups seek to exploit.62

Upholding Fundamental Rights: While countering hate speech and incitement is necessary, strategies must be carefully designed to protect freedom of expression and assembly, avoiding measures that could be perceived as suppressing legitimate dissent.69

Building democratic resilience should be understood not as implementing a single policy, but as cultivating a complex societal ecosystem. In this ecosystem, institutions are perceived as legitimate and effective, citizens are engaged, informed, and capable of critical thinking, diversity is embraced as a strength, channels exist for constructively addressing grievances, and extremist narratives struggle to find fertile ground. Achieving this requires a sustained, multi-sectoral commitment involving government, civil society, educators, the media, and individual citizens. It recognizes that the strongest defense against anti-democratic forces lies in the health, inclusivity, and vitality of democracy itself. Short-term, security-focused responses, while sometimes necessary, are insufficient without long-term investment in these foundational elements of a resilient democratic society.

Conclusion

The post-World War II recruitment of German scientists and intelligence personnel, including individuals with significant Nazi affiliations, through programs like Operation Paperclip and the establishment of the Gehlen Organization, represents a complex and ethically fraught chapter in Cold War history. The analysis of available evidence indicates that these actions were driven primarily by the perceived strategic imperatives of the burgeoning conflict with the Soviet Union – specifically, the desire to acquire advanced technology and crucial intelligence capabilities while denying them to a rival superpower. While the consequence was undeniably the integration of individuals linked to Nazi atrocities into sensitive Western structures, often facilitated by the deliberate obscuring of their pasts, the evidence does not strongly support a primary motive of intentional ideological "infiltration" through these specific programs. Rather, it points to a pragmatic, if morally compromised, pursuit of national security advantage in a high-stakes geopolitical contest. The failure of denazification efforts, similarly influenced by Cold War priorities and practical challenges, further complicated the post-war landscape, allowing continuity of personnel in various sectors of West German society and potentially hindering a full reckoning with the Nazi past.

Drawing analogies between this historical period and the contemporary rise of global far-right networks reveals both pertinent parallels and crucial distinctions. Similarities include the transnational nature of actors and ideologies, the exploitation of crises and societal anxieties, the key role of technology (albeit different types), and the recurrence of ethical compromises by state or influential actors. However, significant divergences exist in the relationship between extremists and the state, primary motivations, personnel types, and organizational structures. Modern far-right networks, often decentralized and operating in opposition to existing liberal democratic states, leverage digital technology to build global communities based on shared grievances and ideologies like nativism, authoritarianism, and anti-democracy, frequently employing conspiracy theories and aiming to influence or upend the current political order.

Learning from both the historical handling of extremism and contemporary expert analysis suggests that defending non-authoritarian societies requires a comprehensive and sustained strategy. This strategy must move beyond purely reactive security measures to embrace a "whole-of-society" approach. Key pillars include: proactive prevention efforts addressing root causes and building resilience through education and inclusion; targeted intervention programs for at-risk individuals; robust but democratically accountable law enforcement and intelligence actions against illegal extremist activities; dedicated measures to counter online disinformation and network building; unequivocal condemnation of extremism by political leaders; and, crucially, long-term investment in strengthening democratic institutions, fostering social cohesion, promoting critical media consumption, and addressing underlying socio-economic fissures.

Ultimately, the history of post-war recruitment and the challenge of modern extremism underscore the enduring tension between perceived national security needs and fundamental democratic values and ethical principles. It highlights the adaptability of extremist ideologies and the constant need for vigilance, critical self-reflection, and proactive measures to safeguard open societies. Understanding the complex, often uncomfortable, compromises of the past is vital for navigating the challenges of the present and future, ensuring that the pursuit of security does not come at the cost of the democratic principles it aims to protect.

Works cited

Denazification - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denazification

the failed post-war experiment: how contemporary scholars address the impact of allied denazification on - Carroll Collected, accessed April 16, 2025, https://collected.jcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=mastersessays

Project Paperclip and American Rocketry after World War II | National Air and Space Museum, accessed April 16, 2025, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/project-paperclip-and-american-rocketry-after-world-war-ii

What Was Operation Paperclip? | HISTORY, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/what-was-operation-paperclip

Operation Paperclip Explained: What Hunters Gets Right About Nazis In America, accessed April 16, 2025, https://screenrant.com/hunters-amazon-operation-paperclip-nazis-america-scientists-nasa-explained/

Capitalism's Victor's Justice? The Hidden Stories Behind the Prosecution of Industrialists Post-WWII - Oxford Academic, accessed April 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/book/26719/chapter/195546490/chapter-pdf/53457701/acprof-9780199671144-chapter-8.pdf

561: OPERATION PAPER CLIP: A MORAL PARADOX – Air Marshal's Perspective - 55 NDA, accessed April 16, 2025, https://55nda.com/blogs/anil-khosla/2024/12/17/561-operation-paper-clip-a-moral-paradox/

Why the U.S. Government Brought Nazi Scientists to America After World War II, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-us-government-brought-nazi-scientists-america-after-world-war-ii-180961110/

Operation Paperclip - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Paperclip

From Operation Paperclip to Scientific Advancements | History - Vocal Media, accessed April 16, 2025, https://vocal.media/history/from-operation-paperclip-to-scientific-advancements

Operation OVERCAST Created to Recruit German Scientists (19 JUL 1945) - DVIDS, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.dvidshub.net/news/476098/operation-overcast-created-recruit-german-scientists-19-jul-1945

Operation Paperclip | Definition, History, & World War II | Britannica, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Project-Paperclip

Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Pacific Atrocities Education, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.pacificatrocities.org/book-unit-731-coverup-the-operation-paperclip-of-the-east.html

A10. Operation Paperclip: How German Scientists Were Brought to the US after World War II, accessed April 16, 2025, https://assumptionwise.org/event-5375339

Wernher von Braun and the Nazis | American Experience | Official ..., accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/chasing-moon-wernher-von-braun-and-nazis/

Records of the Secretary of Defense (RG 330) - National Archives, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rg-330-defense-secretary

List of Germans relocated to the US via the Operation Paperclip - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Germans_relocated_to_the_US_via_the_Operation_Paperclip

Memorandum by The Acting Secretary of State to President Truman - Historical Documents - Office of the Historian, accessed April 16, 2025, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1946v05/d448

Gehlen Organization - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gehlen_Organization

Gehlen Organization - German Intelligence Agencies, accessed April 16, 2025, https://irp.fas.org/world/germany/intro/gehlen.htm

Reinhard Gehlen - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinhard_Gehlen

Cold War Spies: General Reinhard Gehlen - Warfare History Network, accessed April 16, 2025, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/cold-war-spies-general-reinhard-gehlen/

en.wikipedia.org, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinhard_Gehlen#:~:text=On%206%20December%201946%2C%20he,SD%2C%20which%20was%20headquartered%20first

THE GUNS OF AUGUST: Nazis, NATO and the Color Revolutions - ИНВИССИН, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.invissin.ru/topics/ukrain_en/the_guns_of_august/

The Secret Operation To Bring Nazi Scientists To America | South Dakota Public Broadcasting, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.sdpb.org/2014-02-15/the-secret-operation-to-bring-nazi-scientists-to-america

Wernher von Braun and the Nazi Rocket Program: An Interview with Michael Neufeld, PhD, of the National Air and Space Museum | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/wernher-von-braun-and-nazi-rocket-program-interview-michael-neufeld-phd-national-air

Analyzing Public Reaction to the Secret Use of Nazi Scientists by the United States Government, accessed April 16, 2025, https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/84559/Kretz%2C%20Hidden%20Among%20Us.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Dr. Mengele, USA Style: Lessons from Human Rights Abuses in Post-World War II America - cosmos + taxis, accessed April 16, 2025, https://cosmosandtaxis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/coyne_hall_ct_vol10_iss9_10.pdf

The Nazis in the space program. - Slate Magazine, accessed April 16, 2025, https://slate.com/technology/2023/08/nasa-nazi-history-von-braun.html

Wernher von Braun: History's most controversial figure? | Opinions - Al Jazeera, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2013/5/3/wernher-von-braun-historys-most-controversial-figure

Wernher von Braun - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wernher_von_Braun

Denazification - (European History – 1945 to Present) - Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed April 16, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/europe-since-1945/denazification

Denazification - AlliiertenMuseum, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.alliiertenmuseum.de/en/thema/denazification/

Denazification – The Holocaust Explained: Designed for schools, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/survival-and-legacy/postwar-trials-and-denazification/de-nazification/

From Destruction to Deliverance: Shifting Allied Policies for the Occupation of Germany 1944-1955, accessed April 16, 2025, https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/corvette/article/view/20114/8911

Problems of Political Reeducation in West Germany, 1945-1960 - Museum of Tolerance, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.museumoftolerance.com/education/archives-and-reference-library/online-resources/simon-wiesenthal-center-annual-volume-4/annual-4-chapter-3.html

Everyday Denazification in Postwar Germany: The Fragebogen and Political Screening during the Allied Occupation. Mikkel Dack | Holocaust and Genocide Studies | Oxford Academic, accessed April 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/hgs/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hgs/dcaf011/8101406?searchresult=1

Introduction - Everyday Denazification in Postwar Germany - Cambridge University Press, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/everyday-denazification-in-postwar-germany/introduction/A315CC23B25AD20AA0B092F5278EF142

Fleeing Nazis shaped Austrian politics for generations after World War II. Regions that witnessed an influx of Nazis fleeing the Soviets after WWII are significantly more right-leaning than other parts of the country. There were no such regional differences in far-right values before World War Two. : r/science - Reddit, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/science/comments/fp7jrv/fleeing_nazis_shaped_austrian_politics_for/

Fascism in the United States - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fascism_in_the_United_States

The far right as social movement | European Societies - MIT Press Direct, accessed April 16, 2025, https://direct.mit.edu/euso/article/21/4/447/127122/The-far-right-as-social-movement

Far-Right Social Media Communication in the Light of Technology Affordances: A Systematic Literature Review - Oxford Academic, accessed April 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/anncom/article/48/1/37/7913160

Full article: Discourse Networks of the Far Right: How Far-Right Actors Become Mainstream in Public Debates - Taylor & Francis Online, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10584609.2024.2308601

Between extremism and freedom of expression: Dealing with non-violent right- wing extremist actors - Migration and Home Affairs, accessed April 16, 2025, https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-10/ran_dealing_with_non-violent_rwe_actors_082021_en.pdf

Hatewatch | Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.splcenter.org/resources/hatewatch/

Dismantling White Supremacy - Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.splcenter.org/racial-justice-issues/dismantling-white-supremacy/

White Nationalist - Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/white-nationalist/

Alt-Right - Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/alt-right/

ADL: Homepage ORG, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.adl.org/

ADL Report Finds High Levels of White Supremacist, Anti-Government Activity in the Pacific Northwest, accessed April 16, 2025, https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2025R1/Downloads/PublicTestimonyDocument/136463

Societal Threats and Declining Democratic Resilience: The New Extremism Landscape, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.crestadvisory.com/post/societal-threats-and-declining-democratic-resilience-the-new-extremism-landscape

Extremist and Far-right Threats to the 2022 Midterms - YouTube, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyUW_wDXVuc

From Margins to Mainstream: How Extremism Has Conquered the Political Middle, accessed April 16, 2025, https://icct.nl/publication/margins-mainstream-how-extremism-has-conquered-political-middle

The Globalization of Far-Right Extremism: An Investigative Report - Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, accessed April 16, 2025, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-globalization-of-far-right-extremism-an-investigative-report/

The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States - CSIS, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/rise-far-right-extremism-united-states

Anti-democratic politics in the US | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/political-science/anti-democratic-politics-us

Combating Political Violence | George W. Bush Presidential Center, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.bushcenter.org/catalyst/creating-more-perfect-union/kleinfeld-combating-political-violence

Countering organized violence in the United States - Brookings Institution, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/countering-organized-violence-in-the-united-states/

Far-right parties and discourse in Europe - European Network Against Racism, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.enar-eu.org/wp-content/uploads/publication_far_right_en_final.pdf

Action plan for tackling right-wing extremism, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/DVE/220725%201.1%20Action%20plan%20for%20tackling%20right-wing%20extremism.pdf

Anti-Defamation League - Wikipedia, accessed April 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Defamation_League

Pre-World War mentalities resurface with rising political extremism - GIS Reports, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/political-extremism/

PREVENTING VIOLENT EXTREMISM - United Nations Development Programme, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Discussion%20Paper%20-%20Preventing%20Violent%20Extremism%20by%20Promoting%20Inclusive%20%20Development.pdf

Fighting Terrorism: The Democracy Advantage, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/fighting-terrorism-the-democracy-advantage/

Countering Disinformation Effectively: An Evidence-Based Policy Guide, accessed April 16, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/01/countering-disinformation-effectively-an-evidence-based-policy-guide

The Role of Civil Society in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalization that Lead to Terrorism - Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe | OSCE, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/2/2/400241_1.pdf

Counter-Terrorism Module 2 Key Issues: Radicalization & Violent Extremism, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/terrorism/module-2/key-issues/radicalization-violent-extremism.html

COUNTERING VIOLENT EXTREMISM: - National War College, accessed April 16, 2025, https://nwc.ndu.edu/Portals/71/Images/Publications/Family_Counselling_De_radicalization_and.pdf?ver=POmMmM26j53jLqNg1o71wA%3D%3D

Government strengthens approach to counter extremism - GOV.UK, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-strengthens-approach-to-counter-extremism